Nature of the country occupied by the natives—Distribution of the natives in local groups—Names given to the local groups—Local Totemic groups—The Alatunja or head man of each group and his powers—The position of Alatunja a hereditary one—Strong influence of custom—Possibility of introduction of changes in regard to custom—Councils of old men—Medicine men—Life in camp—Hunting customs—Food and method of cooking—Tracking powers—Counting and reckoning of time—General account of the more common weapons and implements—Clothing—Fighting—Local Totemic groups—Variation in customs amongst different Australian tribes—Personal appearance of the natives—Cicatrices—Measurements of the body—Moral character—Infanticide—Twins—Dread of evil magic.

THE native tribes with which we are dealing occupy an area in the centre of the Australian continent which, roughly speaking, is not less than 700 miles in length from north to south, and stretches out east and west of the transcontinental telegraph line, covering an unknown extent of country in either direction. The nature of the country varies much in different parts of this large area; at Lake Eyre, in the south, it is actually below sea-level. As we travel northwards for between 300 and 400 miles, the land gradually rises until it reaches an elevation of 2,000 feet; and to this southern part of the country the name of the Lower Steppes may appropriately be given. Northwards from this lies an elevated plateau forming the Higher Steppes, the southern limit of which is roughly outlined by the James and Macdonnell p. 2 ranges, which run across from east to west for a distance of 400 miles.

The rivers which rise in the Higher Steppes find their way to the south, passing through deep gaps in the mountain ranges and then meandering slowly across the Lower Steppes until they dwindle away and are lost amongst the southern sandy flats, or perhaps reach the great depressed area centreing in the salt bed of Lake Eyre.

Away to the south and west of this steppe land lies a vast area of true desert region, crossed by no river courses, but with mile after mile of monotonous sand-hills covered with porcupine grass, or with long stretches of country where thick belts of almost impenetrable mulga scrub stretch across.

We may first of all briefly outline, as follows, the nature of the country occupied by the tribes with which we are dealing. At the present day the transcontinental railway line, after running along close by the southern edge of Lake Eyre, lands the traveller at a small township called Oodnadatta, which is the present northern terminus of the line, and lies about 680 miles to the north of Adelaide. Beyond this transit is by horse or camel; and right across the centre of the continent runs a track following closely the course of the single wire which serves to maintain, as yet, the only telegraphic communication between Australia and Europe. From Oodnadatta to Charlotte Waters stretches a long succession of gibber 1 plains, where, mile after mile, the ground is covered with brown and purple stones, often set close together as if they formed a tesselated pavement stretching away to the horizon. They are formed by the disintegration of a thin stratum of rock, called the Desert Sandstone, which forms the horizontal capping of low terraced hills, from which every here and there a dry watercourse, fringed with a thin belt of mulga-trees, comes down on to the plain across which it meanders for a few miles and then dies away.

The only streams of any importance in this part of the country are the Alberga, Stevenson, and Hamilton, which run

across from the west and unite to form the Macumba River, which in times of flood empties itself into Lake Eyre. It is only very rarely that the rainfall is sufficient to fill the beds of these three streams; as a general rule a local flood occurs in one or other of them, but on rare occasions a widely distributed rainfall may fill the creeks and also the Finke river, which flows south from the Macdonnell range, which lies away to the north. When such a flood does occur—and this only takes place at long and irregular intervals of time—then the ordinary river beds are not deep enough to hold the body of water descending from the various ranges in which the tributary streams take their rise. Under these conditions the flood waters spread far and wide over the low-lying lands around the river courses. Down the river beds the water sweeps along, bearing with it uprooted trees and great masses of débris, and carving out for itself new channels. Against opposing obstacles the flood wrack is piled up in heaps—in fact, for months afterwards débris amongst the branches of trees growing in and about the watercourses indicates the height reached by the flood. What has been for often many months dry and parched-up land is suddenly transformed into a vast sheet of water. It is only however a matter of a very short time; the rainfall ceases and rapidly the water sinks. For a few days the creeks will run, but soon the surface flow ceases and only the scattered deeper holes retain the water. The sun once more shines hotly, and in the damp ground seeds which have lain dormant for months germinate, and, as if by magic, the once arid land becomes covered with luxuriant herbage. Birds, frogs, lizards and insects of all kinds can be seen and heard where before everything was parched and silent. Plants and animals alike make the most of the brief time in which they can grow and reproduce, and with them it is simply a case of a keen struggle, not so much against living enemies, as against their physical environment. If a plant can, for example, before all the surface moisture is exhausted, grow to such a size that its roots can penetrate to a considerable distance below the surface to where the sandy soil remains cool, then it has a chance of surviving; if not, it must perish. In just the same way amongst animals, those which can grow p. 5 rapidly, and so can, as in the case of the frogs, reach a stage at which they are able to burrow while the banks of the waterhole in which they live are damp, will survive.

It is difficult to realise without having seen it the contrast between the Steppe lands of Australia in dry and rainy seasons. In the former the scene is one of desolation; the sun shines down hotly on stony plains or yellow sandy ground, on which grow wiry shrubs and small tussocks of grass, not closely set together, as in moister country, but separated from one another, so that in any patch of ground the number of individual plants can be counted. The sharp, thin shadows of the wiry scrub fall on the yellow ground, which shows no sign of animal life except for the little ant-hills, thousands of whose occupants are engaged in rushing about in apparently hopeless confusion, or piling leaves or seeds in regular order around the entrance to their burrows. A “desert oak” 1 or an acacia-tree may now and then afford a scanty shade, but for weeks together no clouds hide the brightness of the sun by day or of the stars by night.

Amongst the ranges which rise from the Higher Steppes the scenery is of a very different nature. Here, wild and rugged quartzite ranges, from which at intervals rise great rounded bluffs or sharply outlined peaks, reaching in some instances a height of 5,000 feet, run roughly parallel to one another, east and west, for between 300 and 400 miles. These ridges are separated from one another by valleys, varying in width from 200 or 300 yards to twenty miles, where the soil is hard and yellow and the scrub which thinly covers it is just like that of the Lower Steppes. The river courses run approximately north and south, and, as the watershed lies to the north of the main ranges, they have to cut at right angles across the latter. This they do in gorges, which are often deep and narrow. Some of them, except at flood times, are dry and afford the only means of traversing the ranges; others are constantly filled with water which, sheltered from the heat of the sun, remains in the dark waterholes when

elsewhere the watercourses are quite dry. The scenery amongst the ranges is by no means devoid of beauty. The rugged red rocks, with here and there patches of pines or cycads, or stray gum-trees with pure white trunks, stand out sharply against the clear sky. In the gorges the rocks rise abruptly from the sides of the waterpools, leaving often only a thin strip of blue sky visible overhead. In some cases the gorge will run for half a mile across the range like a zigzag cleft not more than ten or twelve feet wide.

In addition to the Steppe lands there lies away to the south and west the true desert country where there are no watercourses other than the very insignificant ones which run for at most a mile or two across the sandy flats which surround the base of isolated hills such as Mount Olga or Ayers Rock. In this region the only water is to be found in rock holes on the bare hills which every now and then rise out above the sand-hills and the mulga-covered flats. Nothing could be more dreary than this country; there is simply a long succession of sand-hills covered with tussocks of porcupine grass, the leaves of which resemble knitting-needles radiating from a huge pin-cushion, or, where the sand-hills die down, there is a flat stretch of hard plain country, with sometimes belts of desert oaks, or, more often, dreary mulga scrub. In this desert country there is not much game; small rats and lizards can be found, and these the native catches by setting fire to the porcupine grass and so driving them from one tussock to another; but he must often find it no easy matter to secure food enough to live upon. In times of drought, which very frequently occur, the life of these sand-hill blacks must be a hard one. Every now and then there are found, right in the heart of the sand-hills, small patches of limestone, in each of which is a deep pit-like excavation, at the bottom of which there may or may not be a little pool of water, though such “native wells,” as they are called, are of rare occurrence and are the remnants of old mound springs. More likely than not, the little water which one does contain is foul with the decaying carcase of a dingo which has ventured down for a drink and has been too weak to clamber out again. The most characteristic feature of the desert country, next to the sand-hills, are the remains of p. 7 what have once been lakes, but are now simply level plains of glistening white salt, hemmed in with low hills covered with dreary scrub. Around these there is no sign of life, and the most perfect silence reigns.

Such is the general nature of the great area of Steppe and desert land inhabited by the Central Australian natives. In times of long-continued drought, when food and water 1 are both scarce, he has to suffer privation; but under ordinary circumstances, except in the desert country, where it can never be very pleasant, his life is by no means a miserable or a very hard one. Kangaroo, rock-wallabies, emus, and other forms of game are not scarce, and often fall a prey to his spear and boomerang, while smaller animals, such as rats and lizards, are constantly caught without any difficulty by the women, who also secure large quantities of grass seeds and tubers, and, when they are in season, fruits, such as that of the quandong or native plum.

Each of the various tribes speaks a distinct dialect, and regards itself as the possessor of the country in which it lives. In the more southern parts, where they have been long in contact with the white man, not only have their numbers diminished rapidly, but the natives who still remain are but poor representatives of their race, having lost all or nearly all of their old customs and traditions. With the spread of the white man it can only be a matter of comparatively a few years before the same fate will befall the remaining tribes, which are as yet fortunately too far removed from white settlements of any size to have become degraded. However kindly disposed the white settler may be, his advent at once and of necessity introduces a disturbing element into the environment of the native, and from that moment degeneration sets in, no matter how friendly may be the relations between the Aborigine and the new-comers. The chance of securing cast-off clothing, food, tobacco, and perhaps also knives and tomahawks, in return for services rendered to the settler, at once attracts the native into the vicinity of any settlement however small. The young men, under the new influence, become freed from the wholesome restraint of the older men, who are all-powerful in the normal condition of the tribe. The strict moral code, which is certainly enforced in their natural state, is set on one side, and nothing is adopted in place of it. The old men see with sorrow that the younger ones do not care for the time-honoured traditions of their fathers, and refuse to hand them on to successors who, according to their ideas, are not worthy to be trusted with them; vice, disease, and difficulty in securing the natural food, which is driven away by the settlers, rapidly diminish their numbers, and when the remnant of the tribe is gathered into some mission station, under conditions as far removed as they can well be from their natural ones, it is too late to learn anything of the customs which once governed tribal life.

Fortunately from this point of view the interior of the continent is not easily accessible, or rather its climate is too dry and the water supply too meagre and untrustworthy, to admit as yet of rapid settlement, and therefore the natives, in many parts, are practically still left to wander over the land which the white man does not venture to inhabit, and amongst them may still be found tribes holding firmly to the beliefs and customs of their ancestors.

If now we take the Arunta tribe as an example, we find that the natives are distributed in a large number of small local groups, each of which occupies, and is supposed to possess, a given area of country, the boundaries of which are well known to the natives. In speaking of themselves, the natives will refer to these local groups by the name of the locality which each of them inhabits. Thus, for example, the natives living at Idracowra, as the white men call it, will be called ertwa Iturkawura opmira, which means men of the Iturkawura camp; those living at Henbury on the Finke will be called ertwa Waingakama opmira, which means men of the Waingakama (Henbury) camp. Often also a number of separate groups occupying a larger district will be spoken of collectively by one name, as, for example, the groups living along the Finke River are often spoken of as Larapinta men, p. 9 from the native name of the river. In addition to this the natives speak of different divisions of the tribe according to the direction of the country which they occupy. Thus the east side is called Iknura ambianya, the west side Aldorla ambianya, the south-west Antikera ambianya, the north side Yirira ambianya, the south-east side Urlewa ambianya. Ertwa iknura ambianya is applied to men living on the east, and so on.

Still further examination of each local group reveals the fact that it is composed largely, but not entirely, of individuals who describe themselves by the name of some one animal or plant. Thus there will be one area which belongs to a group of men who call themselves kangaroo men, another belonging to emu men, another to Hakea flower men, and so on, almost every animal and plant which is found in the country having its representative amongst the human inhabitants. The area of country which is occupied by each of these, which will be spoken of as local Totemic groups, varies to a considerable extent, but is never very large, the most extensive one with which we are acquainted being that of the witchetty grub people of the Alice Springs district. This group at the present time is represented by exactly forty individuals (men, women, and children), and the area of which they are recognised as the proprietors extends over about 100 square miles. In contrast to this, one particular group of “plum-tree” people is only, at the present day, represented by one solitary individual, and he is the proprietor of only a few square miles.

With these local groups we shall subsequently deal in detail, all that need be added here in regard to them is that groups of the same designation are found in many parts of the district occupied by the tribe. For example, there are various local groups of kangaroo people, and each one of these groups has its head man or, as the natives themselves call him, its Alatunja. 1 However small in numbers a local group may be it always has its Alatunja.

Within the narrow limits of his own group the local head man or Alatunja takes the lead; outside of his group no head man has of necessity any special power. If he has any generally-recognised authority, as some of them undoubtedly have, this is due to the fact that he is either the head of a numerically important group or is himself famous for his skill in hunting or fighting, or for his knowledge of the ancient traditions and customs of the tribe. Old age does not by itself confer distinction, but only when combined with special ability. There is no such thing as a chief of the tribe, nor indeed is there any individual to whom the term chief can be applied.

The authority which is wielded by an Alatunja is of a somewhat vague nature. He has no definite power over the persons of the individuals who are members of his group. He it is who calls together the elder men, who always consult concerning any important business, such as the holding of sacred ceremonies or the punishment of individuals who have broken tribal custom, and his opinion carries an amount of weight which depends upon his reputation. He is not of necessity recognised as the most important member of the council whose judgment must be followed, though, if he be old and distinguished, then he will have great influence. Perhaps the best way of expressing the matter is to say that the Alatunja has, ex-officio, a position which, if he be a man of personal ability, but only in that case, enables him to wield considerable power not only over the members of his own group, but over those of neighbouring groups whose head men are inferior in personal ability to himself.

The Alatunja is not chosen for the position because of his ability; the post is one which, within certain limits, is hereditary, passing from father to son, always provided that the man is of the proper designation—that is, for example, in a kangaroo group the Alatunja must of necessity be a kangaroo man. To take the Alice Springs group as an example, the holder of the office must be a witchetty grub man, and he must also be old enough to be considered capable of taking the lead in certain ceremonies, and must of necessity be a fully initiated man. The present Alatunja inherited the post p. 11 from his father, who had previously inherited it from his father. The present holder has no son who is yet old enough to be an Alatunja, so that if he were to die within the course of the next two or three years his brother would hold the position, which would, however, on the death of this brother, revert to the present holder's son. It of course occasionally happens that the Alatunja has no son to succeed him, in which case he will before dying nominate the individual whom he desires to succeed him, who will always be either a brother or a brother's son. The Alatunjaship always descends in the male line, and we are not aware of anything which can be regarded as the precise equivalent of this position in other Australian tribes, a fact which is to be associated with the strong development of the local groups in this part of the continent.

The most important function of the Alatunja is to take charge of what we may call the sacred store-house, which has usually the form of a cleft in some rocky range, or a special hole in the ground, in which, concealed from view, are kept the sacred objects of the group. Near to this store-house, which is called an Ertnatulunga, no woman, child, or uninitiated man dares venture on pain of death.

At intervals of time, and when determined upon by the Alatunja, the members of the group perform a special ceremony, called Intichiuma, which will be described later on in detail, and the object of which is to increase the supply of the animal or plant bearing the name of the particular group which performs the ceremony. Each group has an Intichiuma of its own, which can only be taken part in by initiated men bearing the group name. In the performance of this ceremony the Alatunja takes the leading part; he it is who decides when it is to be performed, and during the celebration the proceedings are carried out under his direction, though he has, while conducting them, to follow out strictly the customs of his ancestors.

As amongst all savage tribes the Australian native is bound hand and foot by custom. What his fathers did before him that he must do. If during the performance of a ceremony his ancestors painted a white line across the forehead, that line he must paint. Any infringement of custom, within p. 12 certain limitations, is visited with sure and often severe punishment. At the same time, rigidly conservative as the native is, it is yet possible for changes to be introduced. We have already pointed out that there are certain men who are especially respected for their ability, and, after watching large numbers of the tribe, at a time when they were assembled together for months to perform certain of their most sacred ceremonies, we have come to the conclusion that at a time such as this, when the older and more powerful men from various groups are met together, and when day by day and night by night around their camp fires they discuss matters of tribal interest, it is quite possible for changes of custom to be introduced. At the present moment, for example, an important change in tribal organisation is gradually spreading through the tribe from north to south. Every now and then a man arises of superior ability to his fellows. When large numbers of the tribe are gathered together—at least it was so on the special occasion to which we allude—one or two of the older men are at once seen to wield a special influence over the others. Everything, as we have before said, does not depend upon age. At this gathering, for example, some of the oldest men were of no account; but, on the other hand, others not so old as they were, but more learned in ancient lore or more skilled in matters of magic, were looked up to by the others, and they it was who settled everything. It must, however, be understood that we have no definite proof to bring forward of the actual introduction by this means of any fundamental change of custom. The only thing that we can say is that, after carefully watching the natives during the performance of their ceremonies and endeavouring as best we could to enter into their feelings, to think as they did, and to become for the time being one of themselves, we came to the conclusion that if one or two of the most powerful men settled upon the advisability of introducing some change, even an important one, it would be quite possible for this to be agreed upon and carried out. That changes have been introduced, in fact, are still being introduced, is a matter of certainty; the difficulty to be explained is, how in face of the rigid conservatism of the native, which may be said to be one of his leading features, such changes can possibly even be mooted. The only possible chance is by means of the old men, and, in the case of the Arunta people, amongst whom the local feeling is very strong, they have opportunities of a special nature. Without belonging to the same group, men who inhabit localities close to one another are more closely associated than men living at a distance from one another, and, as a matter of fact, this local bond is strongly marked—indeed so marked was it during the performance of their sacred ceremonies that we constantly found it necessary to use the term “local relationship.” Groups which are contiguous locally are constantly meeting to perform ceremonies; and among the Alatunjas who thus come together and direct proceedings there is perfectly sure, every now and again, to be one who stands pre-eminent by reason of superior ability, and to him, especially on an occasion such as this, great respect is always paid. It would be by no means impossible for him to propose to the other older men the introduction of a change, which, after discussing it, the Alatunjas of the local groups gathered together might come to the conclusion was a good one, and, if they did so, then it would be adopted in that district. After a time a still larger meeting of the tribe, with head men from a still wider area—a meeting such as the Engwura, which is described in the following pages—might be held. At this the change locally introduced would, without fail, be discussed. The man who first started it would certainly have the support of his local friends, provided they had in the first instance agreed upon the advisability of its introduction, and not only this, but the chances are that he would have the support of the head men of other local groups of the same designation as his own. Everything would, in fact, depend upon the status of the original proposer of the change; but, granted the existence of a man with sufficient ability to think out the details of any change, then, owing partly to the strong development of the local feeling, and partly to the feeling of kinship between groups of the same designation, wherever their local habitation may be, it seems quite possible that the markedly conservative tendency of the natives in regard to customs handed down to them from their,

ancestors may every now and then be overcome, and some change, even a radical one, be introduced. The traditions of the tribe indicate, it may be noticed, their recognition of the fact that customs have varied from time to time. They have, for example, traditions dealing with supposed ancestors, some of whom introduced, and others of whom changed, the method of initiation. Tradition also indicates ancestors belonging to particular local groups who changed an older into the present marriage system, and these traditions all deal with special powerful individuals by whom the changes were introduced. It has been stated by writers such as Mr. Curr “that the power which enforces custom in our tribes is for the most part an impersonal one.” 1 Undoubtedly public opinion and the feeling that any violation of tribal custom will bring down upon the guilty person the ridicule and opprobrium of his fellows is a strong, indeed a very strong, influence; but at the same time there is in the tribes with which we are personally acquainted something beyond this. Should any man break through the strict marriage laws, it is not only an “impersonal power” which he has to deal with. The head men of the group or groups concerned consult together with the elder men, and, if the offender, after long consultation, be adjudged guilty and the determination be arrived at that he is to be put to death—a by no means purely hypothetical case—then the same elder men make arrangements to carry the sentence out, and a party, which is called an “ininja,” is organised for the purpose. The offending native is perfectly well aware that he will be dealt with by something much more real than an “impersonal power.” 2

In addition to the Alatunja, there are two other classes of men who are regarded as of especial importance; these are the so-called “medicine men,” and in the second place the men who are supposed to have a special power of communicating with the Iruntarinia or spirits associated with the tribe. Needless to say there are grades of skill recognised amongst the members of these two classes, in much the same way as we recognise differences of ability amongst members of the medical profession. In subsequent chapters we shall deal in detail with these three special types; meanwhile in this general résumé it is sufficient to note that they have a definite standing and are regarded as, in certain ways, superior to the other men of the tribe. It may, however, be pointed out that, while every group has its Alatunja, there is no necessity for each to have either a medicine or an Iruntarinia man, and that in regard to the position of the latter there is no such thing as hereditary succession.

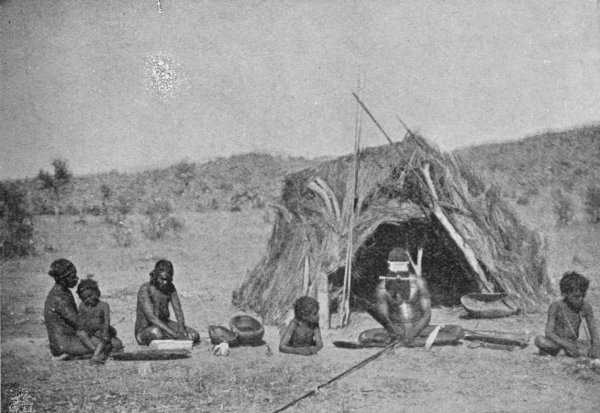

Turning again to the group, we find that the members of this wander, perhaps in small parties of one or two families, often, for example, two or more brothers with their wives and children, over the land which they own, camping at favourite spots where the presence of waterholes, with their accompaniment of vegetable and animal food, enables them to supply their wants. 1

In their ordinary condition the natives are almost completely naked, which is all the more strange as kangaroo and wallaby are not by any means scarce, and one would think that their fur would be of no little use and comfort in the winter time, when, under the perfectly clear sky, which often remains cloudless for weeks together, the radiation is so great that at night-time the temperature falls several degrees below freezing point. The idea of making any kind of clothing as a protection against cold does not appear to have entered the native mind, though he is keen enough upon securing the Government blanket when he can get one, or, in fact, any stray cast-off clothing of the white man. The latter is however worn as much from motives of vanity as from a desire for warmth; a lubra with nothing on except an ancient straw hat and an old pair of boots is perfectly happy. The very kindness of the white man who supplies him, in outlying parts, with stray bits of clothing is by no means conducive to the longevity of the native. If you give a black fellow, say a woollen shirt, he will perhaps wear it for a day or two, after that his wife will be adorned with it, and then, in return for perhaps a little food, it will be passed on to a friend. The natural result is that, no sooner do the natives come into contact with white men, than phthisis and other diseases soon make their appearance, and, after a comparatively short time, all that can be done is to gather the few remnants of the tribe into some mission station where the path to final extinction may be made as pleasant as possible.

source : http://www.sacred-texts.com